The Journal Of People + Strategy

The End of Executive Coaching?

The Journal Of People + Strategy

Click here to download the article.

One-to-one coaching can be powerful and beneficial for both individuals and organizations. But to realize that potential, coaching must take four key steps to adapt.

by David Reimer, the executive editor of People + Strategy and the CEO of The ExCo Group.

This is not an article about ChatGPT.

It is an essay about the structural and methodological limitations of the executive coaching industry as organizations attempt to build future-ready leaders. While the field has spent decades gaining broad acceptance, these limitations risk marginalizing coaching once again. The road to 2030 is riddled with new uncertainties for leaders and managers – they’ve inherited past complexities while adding new ones to the list, seemingly daily. Executive coaching has not evolved as rapidly, yet methodological updates, technologies and measurement factors provide a genuine opportunity for reinvention. L&D and HR professionals have a window to break through the flaws in traditional use-case coaching models, in effect fast-tracking the industry’s adaptation to deliver a different kind of individual and enterprise impact.

Two caveats up front. First, the executive coaching “industry” is atomized and vast. Globally, there are somewhere between 71,0001 and 5,500,0002 executive coaches delivering services. On LinkedIn alone, a search of “executive coach” yields 248,000 individuals serving as coaches. The largest coaching organizations in the world offer networks of roughly 2,000 coaches, most of whom also have private practices and/or subcontract with multiple coaching providers. The reality is that there is no accurate headcount. Similarly, while various reports estimate the industry’s 2019 revenues at between US$2.8B3 and US$15B4, most large organizations today cannot say with certainty how much they spend annually on executive coaching.

Second, I want to acknowledge my bias. I have been in and around the executive development space since 1998. As an executive, I have personally run coaching divisions or had P&L responsibility for people who did so, across Asia Pacific and in the Americas. For the last 13 years, I have served as CEO of a global firm focused primarily on developing senior executives, using former CEOs and experienced GMs as mentors and coaches. My data set, in effect, includes thousands of client experiences and HR professionals’ stories, as well as hundreds of CEO and board conversations about how each constituency defines effective executive coaching. The insights from my years in this field inform my views on measurement, accountability, and impact. One-to-one coaching can be powerful and beneficial for both individuals and organizations. But to realize that potential, it must adapt.

4 STRUCTURAL FLAWS IN THE 20TH-CENTURY COACHING MODEL

Executive coaching achieved widespread acceptance as a development tool for critical talent over the past six decades. While the sector is booming, many of its core tenets rest on assumptions from the largely stable world of the post-World War II era. But those assumptions neither match today’s leadership’s challenges, nor help organizations prepare for the world of 2030.

Four structural flaws pose the greatest risk to the industry. Ranked in order of importance, these are:

Flaw 1: Non-Contextual Methodologies.

Traditional executive coaching remains committed to a non-directive questioning approach. At the risk of oversimplifying, this approach assumes that a) the answers to a client’s attitudes lie within, and b) that by sticking with questions rather than attempting to advise, the coach can help the client reframe and reconsider approaches to their particular problem set, ask themselves why they respond to different stimuli or relationships in certain ways, and adjust how they process the world around them. Over time, the client internalizes these patterns of questioning and establishes a portable toolkit for self-awareness, self-discovery, and self-regulation.

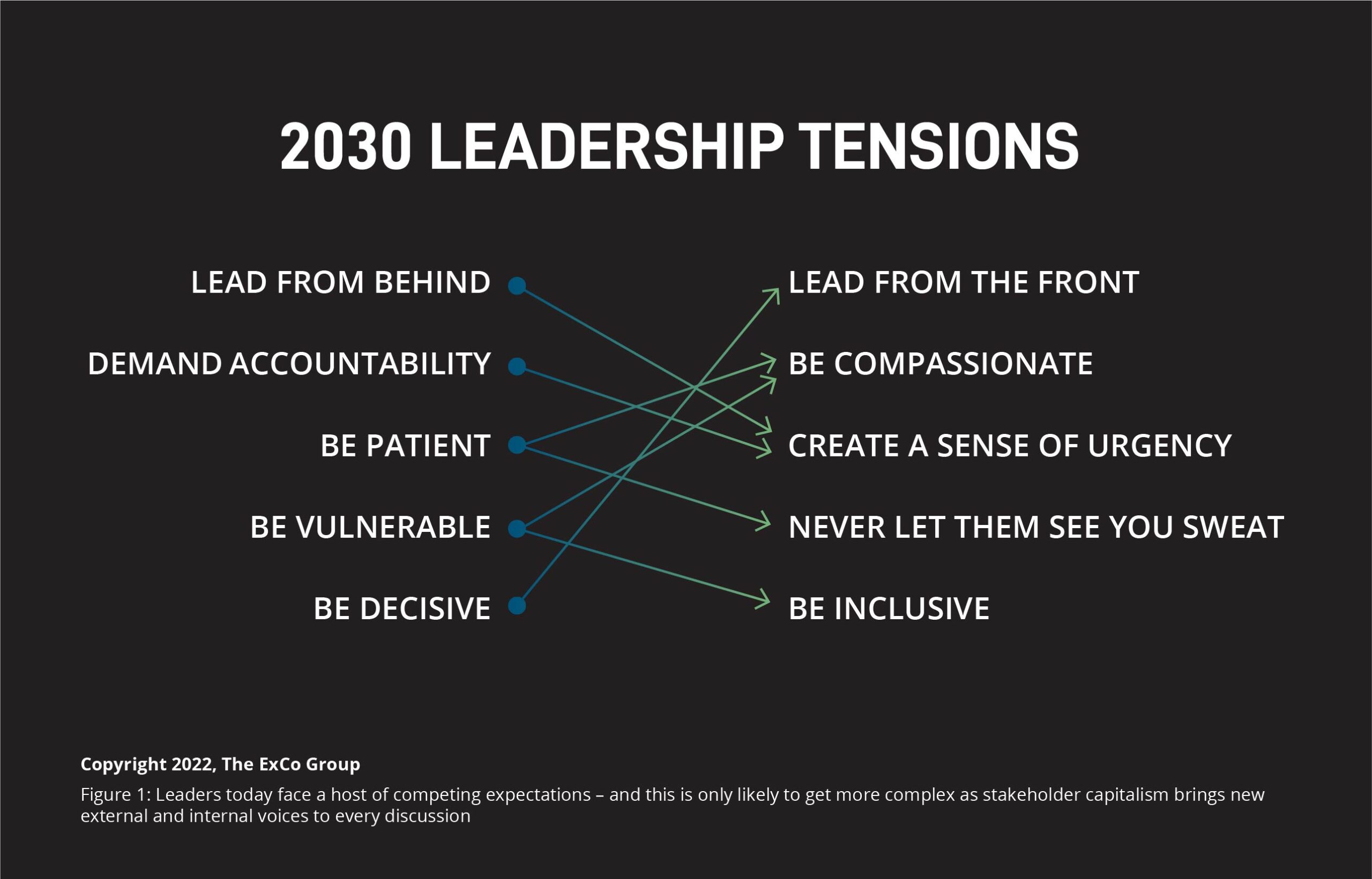

There is nothing wrong, per se, with this approach. But it is not sufficient to the leadership demands of 2030. These last few years have driven, by some estimates, a full generation of change in just three years. Executives today are dealing with problem sets that are not only new to them personally, but that are new to business and organizations collectively, around the planet. The pace is frenetic, the expectation for leaders to keep up is relentless, and many of the new demands are paradoxical. Against this backdrop, non-directive questioning as a stand-alone technique does not address today’s contextual challenges, nor is it sufficiently focused on outcomes.

Conversations defining “good leadership” are not abstract or generalized — they are specific to each company and can be different even within an organization, given the different goals and culture of, say, the legacy part of a business and the riskier, future-oriented divisions. What does stakeholder management mean here? How do we handle politics, religion, and societal conversations in our ecosystem? How is hybrid work impacting how we measure a team’s performance – or how our own performance as leaders will be gauged? How will we respond to employees impacted by divisive legislation when we may have a 50/50 split in opinions on the topic in our boardroom, our C-suite, and our overall employee base?

This makes context king for leaders and managers today. In confronting such problems, managers, and leaders need more than non-directive questions from a coaching partner because it’s likely that the answers to their biggest challenges do not lie within. A coach’s qualifications need to include the expertise to serve as a thought partner for navigating dynamic contexts.

A final – and perhaps more controversial – challenge of traditional methodologies is the limitations of psychometric benchmarks when confronted with real-world messiness. This is not a blanket argument against psychometrics, as they can be helpful in providing insights. Rather, it is an argument that some of the most common uses (particularly in succession conversations) of historic databases as benchmarks to assess future readiness rest on faulty, non-contextual assumptions of what good means now and in the future. Executive-level jobs, and the stakeholders that come with them, require difference from, not sameness with, pre-pandemic leadership archetypes and practices.

Flaw 2: Misaligned Measurement.

The debate over coaching ROI has been problematic. Some organizations avoid the conversation entirely. Others claim returns — inviting deep skepticism — ranging from $50,000 per engagement to 788% of the coaching investment. To be fair, measuring impact is hard. There are fundamental questions of causation and correlation. There are also (though these are mostly red herrings) questions of confidentiality: when does reporting on impact break trust with my client? The industry has largely defaulted to two forms of approximation. The first focuses on activity and client satisfaction: frequency and duration of meetings; and the client’s NPS (or equivalent) rating.

The second method reports on the priorities and general goals of the coaching engagement. This is more substantive than activity and happiness, but goals are not the same thing as measuring impact, and they often suffer from a “translation problem” within organizations. What if HR’s definitions of successful prioritization, for example, are different than the client’s manager’s, or the CEO’s? [See Case Study 1] Whenever major stakeholders are using different scoreboards to define success, declaring victory will be problematic. An experienced and trusted coach helps all parties align upfront, so that the coaching goals are clear – and shared. But that’s still not measuring impact. If the client improves in each identified area… then what?

The industry to date has largely been built on the belief that by helping executives modulate their behaviors, coaching will help them improve the performance of their teams. But hope is not a development strategy. The better question is if the leader has improved, how and where has the organization become more effective, productive, innovative, or profitable as a result of that leader’s evolution?

CASE STUDY 1

When HR opted to get Macy an executive coach, she was coming off a rough patch. Long a top sales performer, she had been subject to an investigation by HR in response to complaints that she was pushing her team too hard, overstepping boundaries on evenings and weekends to get projects done and that she could be excoriating when someone’s work fell short. While the investigation concluded that Macy hadn’t violated company policy, it clearly indicated that her leadership did not role model the desired culture.

In the briefing for the engagement, the HR BP made clear that Macy’s former manager wanted Macy to own her complicity in triggering the investigation. Specifically, the ex-manager wanted her to apologize for having suggested that she had been singled out after a career of positive reviews for behaving in the same way she believed that male executives regularly led. After a first meeting with Macy, it was clear to the coach that she felt betrayed by the organization and was ready to quit.

Over a one-year engagement, Macy adapted her style significantly. She was still meticulous about meeting customer deadlines and finishing projects with a high degree of polish. But she stopped emailing after 6:00 PM and held her weekend communications until late Sunday night. She built up both talent and morale on her team and ensured that she had two ready-now successors under her. Engagement scores rose dramatically. Her new manager felt she was doing a fantastic job. Her team exceeded its sales quota, and Macy landed the company’s largest piece of business that year. And then she turned in her resignation.

Macy’s prior manager indicated his frustration to HR. Not because she had left, but because she had never issued the apology that he had specified as a desired outcome of paying for coaching.

Was this engagement successful or not? How would you measure?

Flaw 3: Structural Fragmentation

The distributed nature of the industry adds difficulty to collating accurate data, even when measurement criteria are clear.

Contractually, many coach-client relationships exist on a metaphorical island. The reason most organizations don’t know how much they spend on executive coaching is because many coaches contract directly with an executive. Most organizations have made great strides to consolidate suppliers, forcing more coaches into sub-contractual relationships with bigger coaching providers, but it doesn’t change the tendency for a coach to view a client as “mine”. That island mentality can exacerbate the problem of misaligned goals, with sourcing, HR, the individual client, the client’s manager, and the coaches themselves having different beliefs about what an ideal outcome means.

Yet changing the status quo is hard. A Fortune 50 CHRO who engaged our firm to lead a 12-person executive committee offsite included in her briefing that, “A lot of the C-suite have coaches. Several are from a firm of IO psychologists. Another one is a former CEO who’s coaching two of our people. And our CFO’s coach is his next-door neighbor. They’re all happy with their coaches but it’s not really helping us function better as a team or as a company. But it’s not worth the political capital to terminate those relationships.” In effect, they were hiring us to create shared goals and generate real-world impact, even though they were spending nearly $2 million a year on executive coaching within the team.

Technologically, since coaching engagements are often distributed across vendors and practitioners, gathering and consolidating data can be an intensely inefficient and highly subjective process. Newer coaching platforms – in particular, BetterUp and Ezra – have created robust data aggregation tools, effectively allowing HR to outsource data analytics on the impact of coaching.

This is a major advancement that was aided by these startups not having to overcome a legacy coaching model in order to imagine a better future. Even so, this potent technological advantage has a short- and medium-term challenge. In the near term, its measurement is still focused on activity and self-reported effectiveness rather than actual impact. Over time, and with more data, that should improve. In the longer term, a battle is brewing on the data front: does the client company get a fancy dashboard that summarizes the data of their employees (the default now), or do they get the underlying data to run their own analytics?

Logistically, the biggest challenge for the field is its lack of barriers to entry, lack of agreed standards of impact, and questions about the real-world abilities of executive coaches to help leaders navigate 2030’s challenges. This has been written about many times by many other authors. The only thing I will add here is that market forces will ultimately decide what constitutes value, and at what price point, from a coach. Presently, the only parts of the market where fees are rising tend to be where coach practitioners bring specialized insight and experience over and above their coaching backgrounds.

Flaw 4: Conflicted Incentives

Most executive coaches are independent contractors whose income derives from coaching engagement fees. This model incentivizes them to extend each individual relationship as long as possible, and penalizes them for ending an engagement, even or especially if they have achieved the initially cited goals. This is not to suggest that most coaches are unethical in seeking coaching extensions. I am merely pointing out that in real-world terms, the business model penalizes a coach for completing an engagement. This should be navigable if a coach is adding long-term value, but to date, the industry has not coalesced around that capability.

SO WHAT DOES ‘BETTER’ LOOK LIKE?

Advisory and coaching in some form have a long-term future. It just won’t look like the past. Practitioners – both in the L&D and HR fields as well as coaches, mentors, and consultants – have a chance to reshape norms to better address emerging needs. Four initial steps will help.

#1 Establish Context and Evolve it Continuously

Coaching metrics, methodology, and measurement must be re-grounded in a company’s strategy. It’s actual strategy, rather than a consulting firm’s HBR-published framework on the seven layers of strategic effectiveness nestled within their fourteen leadership archetypes. Every company faces its own specific headwinds, opportunities, and risk factors. What problem sets do leaders need to solve in your company, and how is that different by level? What stakeholders will they need to manage? What aspects of culture will they need to cherish or change? And all at what pace? The shifting interplay between contextual factors is company-specific if you’re building tomorrow’s leaders instead of yesterday’s leaders.

#2 Extract Emerging Patterns and Understand Core Values

When an organization remains committed to competency models that were fit for purpose in another era, that intransigence hurts the credibility of those charged with leading those conversations in the boardroom or sometimes even with managers and senior executives themselves. As with non-directive questioning, competency models are not “wrong,” but they are insufficient to address the dynamism of the problem set. As one Fortune 25 CEO told us recently, “The job has always been complex and ambiguous, but I don’t think it’s ever been this fluid before.” Given rapidly shifting stakeholder dynamics, unpredictable macro-factors, and fundamental technological and business model changes, competencies are only a single reference point in a leadership development toolkit. Executive coaching must account for at least two other elements.

First, effective coaching should surface emerging issues that are creating new leadership challenges across the organization. Those can then be addressed both individually and collectively.

Second, whatever newfound challenges emerge today, the fluidity cited by that CEO is a reminder that none of us know what the next leadership gauntlet will be. This compromises the value of traditional roadmaps for problem-solving. In effect, we need to better understand a leader’s ability to read a compass when no map is available. Core values provide such a compass. Values drive behaviors, yet as a profession, we’ve focused far less on them than we have on competencies and psychometric profiling. Effective coaching should help create a clearer understanding of the values a leader brings to an uncertain future.

Speaking pragmatically, an HR leader may be stuck with legacy competencies and benchmarks. Perhaps there is a lack of alignment that the current model is obsolete, or perhaps there’s a level of change fatigue that means fixing today’s competencies isn’t an enterprise priority. However, HR leaders can still drive meaningful impact for succession or in broader executive development by engineering around irrelevant terminology to create and measure real-world impact. As hard as this sounds, it is worth the effort if it better serves the organization and bolsters HR’s outcome orientation. [See Case Study 2]

CASE STUDY 2

When the CEO of a global organization felt pressure from his board to prepare for succession, he engaged a well-known leadership consulting firm to develop a template framework to help assess candidates. The template’s elements were stock leadership attributes, with the odd customization– such as “Understands Risk” – open to different interpretations by board members and CEO candidates. The company ended its relationship with the leadership development firm, but the general feeling was that the framework had to stay, imperfect as it was. There wasn’t time or appetite to roll out another.

Behind the scenes, we worked with HR and talent leaders to understand the original intent behind each generic category. We then built a set of interview questions to probe for strategic clarity, operational complexity, and core cultural strengths and weaknesses, before getting to an individual leader’s specific performance. The contextual data from those interviews showed not only how individuals stacked against the top job descriptions but also revealed common areas of ambiguity, avoidance, or outright confusion across the enterprise.

At the end of one year, a new CEO was chosen from the internal candidates. Using the patterns from the interview processes, the CEO and their team created a strategic narrative to drive a new level of clarity across the organization. Then, early in year two, they rolled out a leadership framework that tightly aligned with their strategic narrative. The fit-for-purpose framework illuminated prior areas of confusion, and led to new, company-specific developmental priorities such as “Manages Conflict” and “Listens to Understand”.

The strategic narrative and new framework delivered two outcomes. First, they shifted the company from the bottom quartile to the top quartile in terms of strategic clarity across its ranks. Second, they created a much sharper development guide for the leadership pipeline.

#3 Measure Impact Over Activity (and Don’t Call It ROI!)

In a Fortune 50 undergoing global business model transformation while facing significant investor pressures, a large coaching organization amassed a database of assessment and development areas among the company’s top 300 leaders. Their summary findings: key leadership was divided into empathizers and tyrants. What was needed, they announced, were leaders who could balance empathetic leadership with accountability. But while the firm could diagnose the problem, they were not built to fix it.

One of the traditional criticisms of executive coaching and of consultants, in general, is the ability to diagnose problems but not deliver solutions. HR often gets stuck in the middle of this with the quality of reporting from coaches, and the focus of their engagements. In another Fortune 50 company, coaches reported that 82% of their engagements were focused on the client’s personal development. Of the remaining 18%, priorities for development were behavioral and communications-oriented, rather than being explicitly tied to the organization’s leadership framework.

If HR leaders have an existing leadership framework, they should insist on mapping the priorities of coaching engagements against it. There will still be some degree of personal development, but those should not as a rule exceed 20 percent of all coaching priorities. (If a company is driving transformation, the percentage should be even lower.) Second, be on the lookout for whether the individual priorities that are rolling in start to reveal an unexpected pattern, showing you where people are struggling against it.

In the organization of empathizers/tyrants, we were able to quickly diagnose a problem: executive coaching had over-vectored on making managers more empathetic to their teams (“We’re in it with you, and we know it’s hard”) but had severely underestimated how much their teams needed pragmatic leadership, too. Team members wanted help from managers in terms of leveraging the full power of the matrix on behalf of customers. They needed help with prioritization and accountability, too. Tyrants were failing personally in addition to managing their teams badly. Having long operated in siloes, the shift to matrixed collaboration required them to build entirely new navigation skills. This drove a set of enterprise coaching priorities that now involved decision-making, problem-solving across the matrix, and cooperating in the marketplace in entirely new – and trackable – ways. Once the scoreboard became clear, the majority of leaders were able to demonstrably make the pivot.

The takeaway here: By all means use NPS scores or activity levels to ensure that your executives aren’t disengaged or dissatisfied with their coaching experiences, but measure and report impact using the language and metrics of your real-world leadership and business priorities. [See Case Study 3]

CASE STUDY 3

A century-old Fortune 50 company had struggled to gain insight into the business impact it was getting from the millions of dollars it spent annually on executive coaching. In an attempt to get their arms around the process, they reduced senior-level coaching to two suppliers and asked for standard reporting metrics: frequency of engagements, high-level development priorities, and NPS scores at the beginning and end of each coaching assignment.

In our work with about 20 senior leaders, an enterprise challenge became quickly apparent: decision-making was an extraordinarily complex exercise in stakeholder management within the organization. On average, a leader wanting to drive change needed to align individually with eight or more stakeholders ahead of a formal meeting (a process that often took six to eight weeks, plus another month to schedule the group meeting). Once a change was approved, an additional round of one-on-one conversations had to be held with each stakeholder before moving to implementation. The net result was that getting anything new done in the organization tended to take six to nine months and heroic personal effort. In a rapidly evolving marketplace, we raised this to HR, who broached it with the CEO as a potential Achilles heel.

Together with senior leaders from across the business, HR shepherded a plan for tightening the decision-making process in the short term. In parallel, they developed training for senior leaders and their potential successors on how to drive more efficient decision-making – both as a stakeholder and as the sponsor of a much-needed innovation or improvement. Eighteen months into the process, the organization has reduced the gap between new concepts and eventual implementations by nearly 60 days. Their target is to shave an additional 30 days by the end of 2023.

#4 Build a Leadership Ecosystem, not just Individual Leaders

Executive coaching is, by definition, a 1:1 sport. However, effective coaching is about more than measuring individual impact. Collective targets and high-level areas for impact should be set at the enterprise level up front, and patterns in reporting data should be used to highlight challenges and opportunities around alignment. The art is in finding the level of flexibility that will create a shared understanding of what good leadership means for today and the future while allowing for individual adaptation and pinpoint development solutions to meet the needs of the moment, context, and uniqueness of each leader.

Ideally, this stems from your organization’s leadership framework, firmly rooted in your strategic realities. However, even if that framework isn’t in place (one Fortune 50 had thirteen active leadership frameworks across the company when we first met; a Fortune 10 had none), do not despair. In these cases, expect patterns to emerge from the coaches’ briefings that reveal subtle insights you didn’t know before the engagements began: what problem sets are leaders encountering in common? These are likely different from, though not unrelated to, the reasons you engaged the coach in the first place.

Whether you are starting with a framework (ideal) or working the data to have one emerge (realistic), these shifting definitions of what good looks like serve as powerful, developmental “enterprise backdrops” for gauging impact. Collectively, individual data measured against this backdrop will not only give you a current-state assessment of your leadership ecosystem but will allow you to deliberately shape that ecosystem over time.

SO WHAT IS AI’S IMPACT ON COACHING?

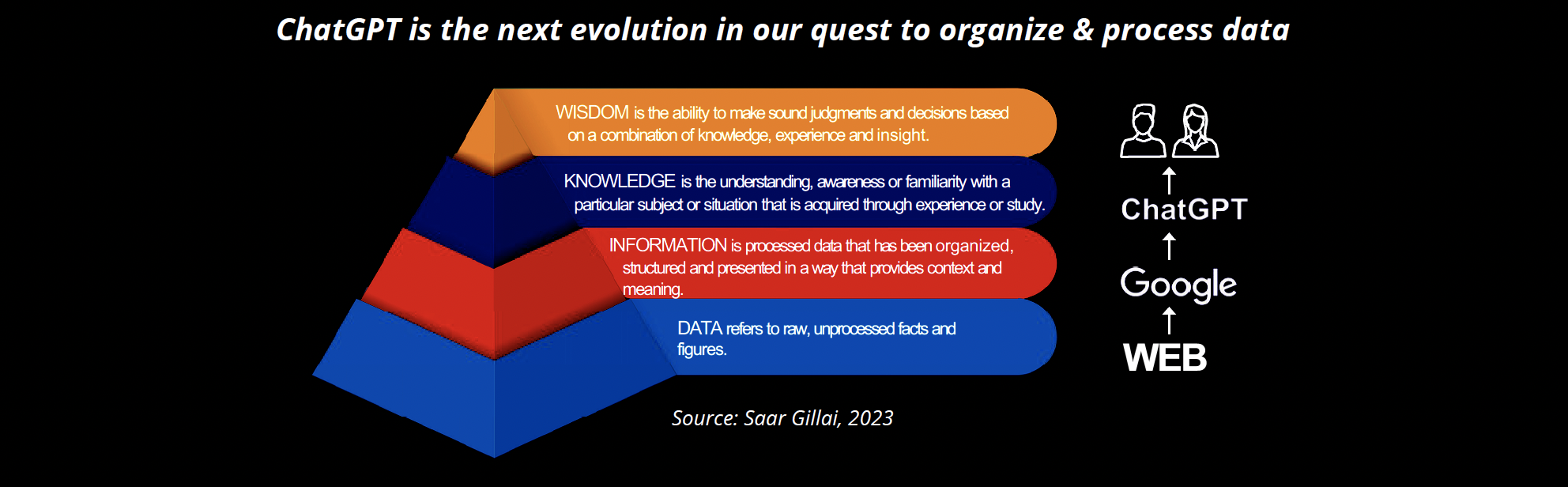

ChatGPT is not the end of executive coaching. Saar Gillai, a veteran technology leader, writes that the missing ingredient from large language models (LLMs) is wisdom. Fast-evolving LLMs put a wealth of information at your fingertips and lay it out in readily accessible prose (or slides, spreadsheets, or visuals). This does put pressure on executive coaches whose primary value, aside from non-directive questioning, is the sharing of information, articles, and the know-how to interpret a particular assessment. LLMs will replace that capability shortly.

Writing this article, I tested ChatGPT about several standard coaching topics, such as time management, strategies for public speaking, and managing an employee with a completely different communication style. In each case, what the application offered was generic and high-level questions about how we would set goals and what we might accomplish through conversation, but nothing that approximated actual coaching. This is not presently an existential threat. AI chatbots that deliver non-directive questioning pose a much greater risk to the profession. This ilk of AI offers the ability to ask non-directive questions in a number of styles, to stimulate genuine self-reflection, and — based upon data from therapeutic use cases — prompt constructive change in some individuals over time.

The real risk to executive coaching is not in standalone AI capability, but a longer-term combination of those two added to an AI/ML overlay to data-mine for emerging patterns and for outcomes/impacts that result from such conversations. In that scenario, if the answers to a manager’s development truly lie within the individuals being coached and do not require outside-in wisdom, executive coaching as an industry should be able to be completely automated.

At present, these three capabilities are more parallel strands than an integrated braid, and therefore only a theoretical threat.

As Gillai pointed out when I asked him about this potentiality, “We’ve been saying that self-driving cars are three years away for at least a decade now. That final 10 percent of execution is the hardest.” In the near term, the executive coaching industry is at greater risk of failing to produce measurable business impact than it is of being displaced by AI.

ADAPTING EXECUTIVE COACHING FOR A 2030 WORLD

Executive coaching as a form of customized, one-to-one development has gained broad general acceptance. By and large, its NPS scores are high, but its actual business impact is opaque. Core elements of the industry don’t lend themselves to measuring outcomes. Meanwhile, nearly every organization faces a reconsideration of what defines effective leadership within its strategic, operational, and cultural contexts. How do we intentionally shape the leadership ecosystem we want, while navigating the leadership ecosystem we have?

Human Resources and Leadership Development executives are in a unique position – a once-in-a-several-generation moment – for reframing and stewarding enterprise-specific goals and desired impacts. Such frameworks will supply external coaches with an accountability and outcome focus that the industry itself has not produced. By taking such steps now, HR and L&D professionals can play an ever more impactful role in shaping their organization’s long-term success.

I have shared ideas in this article, but ultimately the goal is to start a conversation rather than conclude one. It’s why the headline ends with a question mark, not a period. We need productive discussions among the constituents in the leadership ecosystem — boards, C-Suite leaders, HR, consulting firms, and executive coaches — to help everyone more fully align on the use-case of coaching to address a future rife with tensions and rich with possibilities. Companies’ futures will be determined by the effectiveness of their leaders, and it is in our shared interests to ensure that they are as prepared as they can possibly be.